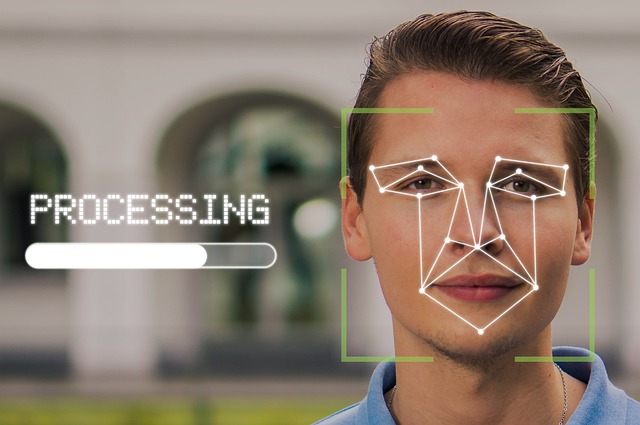

On Dec. 14, the governments of British Columbia, Alberta and Québec ordered facial recognition company Clearview AI to stop collecting — and to delete — images of people obtained without their consent. Discussions about the risks of facial recognition systems that rely on automated face analysis technologies tend to focus on corporations, national governments and law enforcement. But what is of great concern are the ways in which facial reognition and analysis have become integrated into our everyday lives.

Amazon, Microsoft and IBM have stopped supplying facial recognition systems to police departments after studies showed algorithmic bias disproportionately misidentifying people of colour, particularly Black people.

Facebook and Clearview AI have dealt with lawsuits and settlements for building databases of billions of face templates without people’s consent.

In the United Kingdom, police face scrutiny for their use of real-time face recognition in public spaces. The Chinese government tracks its minority Uyghur population through face scanning technologies.

Get news that’s free, independent and based on evidence.

Sign up for newsletter

And yet, to grasp the scope and consequences of these systems we must also pay attention to the casual practices of everyday users who apply face scans and analysis in routine ways that contribute to the erosion of privacy and increase social discrimination and racism.

As a researcher of mobile media visual practices and their historical links to social inequality, I regularly explore how user actions can build or change norms around matters like privacy and identity. In this regard, adoption and use of face analysis systems and products in our everyday lives may be reaching a dangerous tipping point.

Everyday face scans

Open-source algorithms that detect facial features make face analysis or recognition an easy add-on for app developers. We already use facial recognition to unlock our phones or pay for goods. Video cameras incorporated into smart homes use facial recognition to identify visitors as well as personalize screen displays and audio reminders. The auto-focus feature on cellphone cameras includes face detection and tracking, while cloud photo storage generates albums and themed slideshows by matching and grouping faces it recognizes in the images we make.

Face analysis is used by many apps including social media filters and accessories that produce effects like artificially ageing and animating facial features. Self-improvement and forecasting apps for beauty, horoscopes or ethnicity detection also generate advice and conclusions based on facial scans.

But using face analysis systems for horoscopes, selfies or identifying who’s on our front steps can have long-term societal consequences: they can facilitate large-scale surveillance and tracking, while sustaining systemic social inequality.

Casual risks

When repeated over time, such low-stakes and quick-reward uses can inure us to face scanning more generally, opening the door to more expansive systems across differing contexts. We have no control over — and little insight into — who runs those systems and how the data is used.

If we already subject our faces to automated scrutiny, not only with our consent but also with our active participation, then being subjected to similar scans and analysis as we move through public spaces or access services might not seem particularly intrusive.

In addition, our personal use of face analysis technologies contributes directly to the development and implementation of larger systems meant for tracking populations, ranking clients or developing suspect pools for investigations. Companies can collect and share data that connects our images to our identities, or for larger data sets used to train AI systems for face or emotion recognition.

Even if the platform we use restricts such uses, partner products may not abide by the same restrictions. The development of new databases of private individuals can be lucrative, especially when these can comprise multiple face images of each user or can associate images with identifying information, such as account names.

Pseudoscientific digital profiling

But perhaps most troubling, our growing embrace of facial analysis technologies feeds into how they not only determine an individual’s identity, but also their background, character and social value.

Many predictive and diagnostic apps that scan our faces to determine our ethnicity, beauty, wellness, emotions and even our potential earning power build on the disturbing historical pseudosciences of phrenology, physiognomy and eugenics.

These interrelated systems depended to varying degrees on face analysis to justify racial hierarchies, colonization, chattel slavery, forced sterilization and preventative incarceration.

Our use of face analysis technologies can perpetuate these beliefs and biases, implying they have a legitimate place in society. This complicity can then justify similar automated face analysis systems for uses such as screening job applicants or determining criminality.

Building better habits

Regulating how facial recognition systems collect, interpret and distribute biometric data has not kept pace with our everyday use of face scanning and analysis. There has been some policy progress in Europe and parts of the United States, but greater regulation is needed.

In addition, we need to confront our own habits and assumptions. How might we be putting ourselves and others, especially marginalized populations, at risk by making such machine-based scrutiny commonplace?

A few simple adjustments may help us address the creeping assimilation of facial analysis systems in our everyday lives. A good start is to change app and device settings to minimize scanning and sharing. Before downloading apps, research them and read the terms of use.

Resist the short-lived thrill of the latest social media face-effect fad — do we really need to know how we’d look as Pixar characters? Reconsider smart devices equipped with facial recognition technologies. Be aware of the rights of those whose image might be captured on a smart home device — you should always get explicit consent from anyone passing before the lens.

These small changes, if multiplied across users, products and platforms, can protect our data and buy time for greater reflection on the risks, benefits and fair deployment of facial recognition technologies.

By Stephen Monteiro

Assistant Professor of Communication Studies, Concordia University